How Indian ikat differs from uzbek ikat?

There are many examples of uzbek ikat and its features, but do you know anything about Indian ikat? Ikat is one of the oldest known patterned textiles in the world, with a history that spans across multiple cultures and is known to have existed in India since the 6th Century. Traditionally, Ikat was a symbol of status, wealth, power and prestige because of the time and intricate skill involved in the weaving process.

Through timeless, sustainable and functional ready-to-wear Ikat apparels and home furnishings, we at Alesouk are proud to play a part in creating awareness of India’s rich heritage in handlooms while empowering the regional Ikat artisans. Our vision is to revive this dying art by transforming the traditional handloom and to contemporary outfits, accessories and home furnishing in pure handwoven cotton and silk.

The Roots of Indian Ikat

Ikat is a textile art wherein patterns are created by resist dyeing cotton and/or silk yarn before they are woven. This technique is practised across Asia, Latin America and parts of Europe, such as Spain and Holland. Ikat, particularly double ikat, is synonymous with a number of countries including Indonesia and Japan, however, the weaving and dyeing technique has prominent roots in parts of India.

Ikat was once prominent in Tamil Nadu but, today, it is prevalent in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha and Gujarat, where it is known locally by different names. Owing to the lack of written historical documentation it is difficult for historians to pinpoint ikat’s exact country of origin. However, cave frescoes in Ajanta, Maharashtra, that date back to the 7th century CE indicate that ikat has a long history in India.

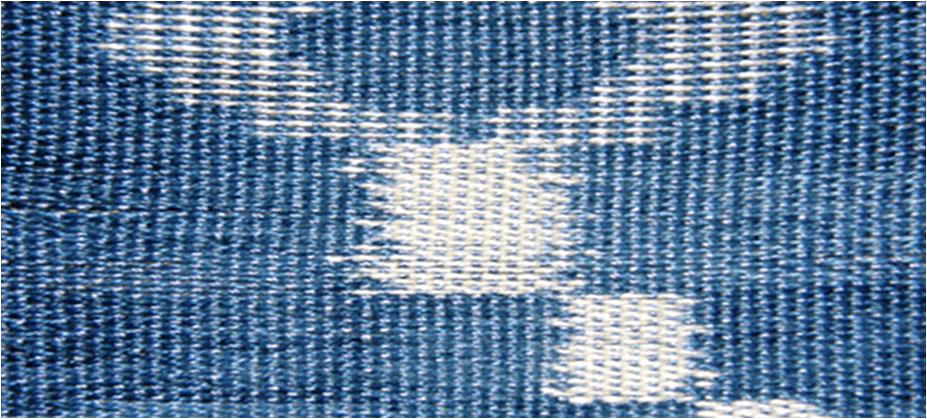

Ikat is similar to tie and dye in regards to the use of resist dyeing to produce elaborate patterns. There are many patterns in ikat, ranging from simple symmetrical motifs to geometric shapes to abstract zoomorphics. Ikat can be categorised into three sub-techniques: warp ikat, weft ikat and double ikat.

Warp Ikat

Warp refers to the yarn that is held within a frame or a loom with exerted tension. Even prior to the use of plain coloured weft that is introduced to the warp to produce fabric, patterns in the warp threads are visible. This technique is widely practised in Koyyalagudem village and Chirala town, Andhra Pradesh and the Nalgonda district of Telangana, a state that was part of Andhra Pradesh until June 2014. As sarees are a sought-after garment by Indian locals and modern-day fashionistas, warp ikat sarees produced in these regions continue to be in high demand.

Weft Ikat

Weft refers to the yarn that produces visible dyed patterns as it is woven into the warps in order to produce fabric. The process of weft ikat is more time consuming compared to warp ikat. This is due to the artisans’ intricate attention to detail in the adjustment of the weft, necessary throughout the weaving process in order to maintain the consistency and clarity of patterns.

Double Ikat

This technique is only produced in India, Japan and Indonesia and incorporates both warp and weft techniques. The warp and weft are both resist-dyed before being worked on on the loom where precision and patience is the key to sustaining the patterns. The incorporation of the warp and weft technique in double ikat is demanding in terms of time and the production process, as reflected in the elaborate patterns and craftsmanship. Weaving in double ikat is so intricate that it can take from seven to nine months to weave the length of a single saree. Within India, the double ikat technique is most renowned in the Nalgonda district of the state of Andhra Pradesh and Patan, Gujarat where it is known as Patan Patola.

As in earlier times, all ikat weaving occurs in the homes of the artisans and is usually a skill that is shared and practised among all members of the family.

How Indian ikat is made?

The loin loom is one of the earliest and most ancient ways of weaving used by women throughout the world. In ancient India, it was considered a sacred act linking the rhythms of the human body through breath, prana or life force, to the weave. One of its warp bars are strapped to the waist and the weaver uses her body weight to create tension. As she inhales the tension is built and the weft is beaten into the warps; as she exhales she lifts the reed creating a shed for throwing the weft thread.

In the loin loom, patterns are woven in as though they are emerging from the weaver’s very being. The act is like a form of yoga, with controlled breathing and disciplined movement, the weaver goes into a state of dhyana meditation, brought on by continuous movement. The woven patterns emerge as a “manifestation of introspective concentration.”

The technique of ikat, known in India as patola, bandha, chitka, and telia rumal – to tie, bind, or link – involves binding the threads of dye-resistant material, and then dyeing them before they are woven. Dyeing plays the most prominent role in the ikat weave. The pattern is not formed by weaving together different threads of colored strands, nor is it printed on fabric. It is made by dyeing the warp and the weft threads before weaving. The designs and patterns are transferred to the fabric straight from the weaver’s imagination.

The magic is in the transportation of pattern from imagination to reality. This is fundamental in weaving ikat. The completed ikat was considered a powerful magical cloth, instilled with the ability to cure, to heal, to purify, and to protect.

“The art of dyeing has always been linked with alchemy, with magic, with transformation, with the mystery of the unknown. This mystique gets reflected on the practitioners. The dyer was an alchemist, who collected herbs, roots, scales of insects, natural minerals, and used these to transform plain cloths of cotton, wool, or silk into myriad hues.”

Ikat developed first in coastal states: Gujarat, Orissa, and Andhra Pradesh through the sea route of Malayan trade. Each of these states are known for their ikat weaves. There are two types of ikat: single-ikat and double-ikat. Single-ikat is where the dye is applied to tied threads of either the warp or the wefts. Double-ikat, the most prized, is where both the warp and the weft threads are tied and dyed and then woven for the pattern to emerge.

PATOLA

Patan, Gujarat is most famous for their double-ikats. Patola is an ancient Indian sacred cloth well known as a luxury export to Malaya and Indonesia as a symbol of nobility and praised for its magical properties. Today, they are made in Patan on a very limited scale. The double-ikat weaving tradition of Gujarat is on the verge of extinction. There are only two families of Jains weaving patolas. Popular motifs were flowers and jewels, elephants, birds, and dancing women. Fine patola in the vagh-na-kunjar (elephants and tiger) motif were extremely popular. Each thread, in its undyed state, needed be counted out, thread by thread, and collected in bundles. Each bundle is then tied and dyed to the particular pattern desired. This work requires two weavers known as salvis. Six to ten inches of fabric are woven each day–that of a sari takes one month.

BANDHA

The ikat technique in Orissa (now known as Odisha) is commonly known as Bandha and referred to as “poetry on the loom.” The Orissan style of ikat has a unique style of flowing designs. The resist tying is done finely on two-thread units giving greater detail and fine curves. Much of the design and color choices are influenced by Lord Jagannath. Every color and symbol represents a concept of the Jagannath cult. The primary colors are white, black, yellow, and red to represent past, present, and the future, to the Vedas and the Gods. Bandha of Orissa stands apart with its natural motifs including floral, fish, animals, and rarely geometrical.

The Sambalpuri Saree is a traditional handwoven Ikat saree that is produced in Bargh, Sambalpur, Sonepur, and nearby districts of Orissa. They are popularly known as PATA using traditional motifs like shankha (shell), chakra (wheel), andphula (flower).

CHITKI AND TELIA RUMAL

The Telugu word for tie and dye is chitki and is what the ikat of Andhra Pradesh is known as. The oldest center in today’s Prakasam District is Chirala, which is most famous for the production of telia rumals, a square shaped patterned cloth. Telia Rumal directly translates to “oily handkerchief”. The cloth is dyed with traditional alizarian dyes, which left an oily smell from which the name derives. They were originally produced for the Muslim market and used as headcloths by Muslim men. Today, the few surviving weavers supply local fishermen who use the cloth as lungis or as turbans. Telia Rumal is a very laborious double-ikat weave. The yarn is treated with oil then tied and dyed. Each of the warp and weft threads are individually positioned on the loom prior to weaving. Only three colors are traditionally used – red, black, and white.