The meaning of Ikat patterns

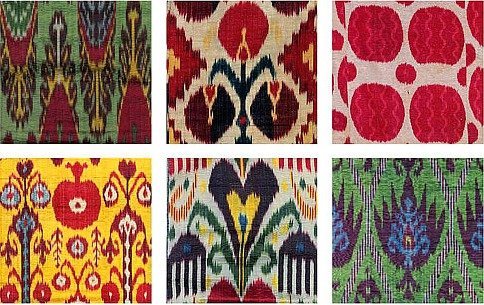

The extraordinarily light and brilliant ikat fabrics carry a weighty burden. Their complex motifs are drawn from a vast repertory of Central Asian pattern, their dynamic lines and rich handling of color are founded in Central Asia’s lengthy and vital artistic tradition. Islamic artists made a conscious effort to describe the pattern of the universe through pure geometry. The great, tile-covered mosques of Bukhara, Samarkand honor the faith of Islam, but each encapsulated section of pattern also represents a distillation of the infinite. The influence of such architecture on the art of the nineteenth century may have been subconscious, but is there all the time. In later ikats, there is a deliberate attempt to incorporate elements taken directly from other arts, while the earliest ikats took more subtle lessons from architectural decoration. Each component within the design of an ikat echoed the ancient culture of Central Asia.

The countries like India, Japan, China and Iran are also owners of the ikat technique. What is the difference between the same techniques in different nations? The “ikat” technique in Uzbekistan differs from all others in the complexity of constructing a pattern, the method of coloring and a wide range of colors.

Patterns created by Uzbek masters are the motifs of the flora and fauna surrounding us. And Indian, for example, patterns include more geometric forms.

Technique “ikat” in Uzbekistan is called “abrband.” From the Persian “abr” – a cloud, “gangs” – to tie. The name of the technology fully reflects its essence.

Symbolic value attached to an image

Many ikats contain triangular patterns with pendant teeth or dangling elements that are variously identified as “combs” or “amulets”. The “comb” design, which has the shape of a weft beating tool, is well known as one of the mirror pattern elements of Central Asian carpets.

Many ikat patterns are dissolved, fragmented, turned around and upside down. Within ikats, the designers have abstracted potent and symbolic images to the point where they are almost unrecognizable, and then combined these shapes in a bewildering variety of patterns. In ikat, the symbolic elements of the pattern are no longer invested with their original meaning.

Over the past few years, Uzbek fabrics have begun to enjoy particular popularity. But the name of the fabric is often confused even by the designers themselves. Let us once and forever put an end to these wanderings in terms. For example, the well-known adras. Is it true that the word adras itself is a combination of cotton and silk? Adras is when cotton is used for the weft, the basis is silk and the weaving technique is two-pedal. It is the combination of cotton and silk threads that make adras be original. But the percentage combination of threads may be different. For example, 70% silk and 30% cotton or vice versa. It depends on the purpose of the fabric. If we are talking about fabric for clothing, then here, so that the fabric was light and pleasant for the body, you must use 70% silk and 30% cotton. The use of fabrics in the interior involves 40% silk and 60% cotton. The fabric will accordingly be heavier, which is required for use in this area. As for the cotton fabric in the technique of “ikat” – this is not adras, but the so-called “Boz”, an analogue of the Russian word “calico”. Thus, the most appropriate name for this fabric will be ikat “coarse calico” or “boz”.

Bekasam is a striped fabric. Components may be different. For example: viscose with cotton or silk with cotton. But in Soviet times, “bekasam” was woven from cotton and polyamide (synthetic fibers that are highly resistant to the external environment) fibers. Externally, “bekasam” looks like fabric “banoras.” But in the manufacture of “Banoras” mainly cotton is used. A cloth is used mainly for sewing light chapans. There are a couple of tissues similar to the above. The first is “alacha.” It is also characterized by a striped pattern. But it has a regional affiliation and is used mainly in Khorezm. Even now, having visited Khorezm, you can see chapans from alachas, put on by the soloists of vocal or dance groups. The second is a “partacha” fabric with a striped pattern. In former times, the fabric was used both for bathrobes and for sewing the burqa among women of average and below average income.

“Bakhmal” is velvet. The weft in the manufacture of «bakhmal» is cotton threads, and the basis is silk. The sophisticated technology of manufacturing “bakhmal” is different from all the others. That is what makes velvet the original one. And of course “shoyi” is 100% silk. This can be felt, just by touching the fabric. It is airy and smooth.

The combination of images used in ikat fabric cannot be read, like a story. One cannot describe what is going on in ikat. There is no presumption of understanding for the viewer. Representation does not equal symbolism; meaning is implicit, rather than explicit. Ikat not only includes familiar images from Central Asian culture; in its method of combining and transforming those images, it is a resonance, a response to the culture itself.